6. Covenants

AN INTRODUCTION TO SERVITUDES, Part II

Covenants

Recall that a covenant is a contract that imposes an obligation to do something or to refrain from doing something on one’s own land. Examples we cited included: a promise by A to B that A will not make commercial use of his property; a promise that A will not build a second story; a promise that A will only build additions that meet with the approval of a homeowner association’s architectural review committee; a promise that A will maintain a wall that separates his property from B’s.

One can distinguish affirmative and negative covenants as, respectively, requiring or prohibiting conduct on the part of the owner of the burdened land. Though some courts treat these two types of covenants differently, we note this difference only in one respect below.

Another distinction, often seen in the case law, is between real covenants and equitable servitudes. This distinction goes back to the difference between law and equity. To make a long and complex story short, we will refer to a covenant as a real covenant when damages are sought for breach and as an equitable servitude when an injunction is sought.

Running with the Land

We deal here with what a court will insist upon before it will decide that a covenant runs to subsequent landowners. That is, when are people who buy land bound by a contract signed by prior owners of that land. As you will see in the cases, this area of the law is in flux. Below we will discuss the traditional requirements. But some courts, and the Third Restatement, are taking the view that many of the traditional elements should be dropped in favor of finding covenants to run whenever “reasonable,” which word applies to the agreement of the original parties and the impact of the covenant today. Because such an analysis tends to replicate many of the features of the traditional analysis, and because many courts adhere to the traditional analysis, we will start there.

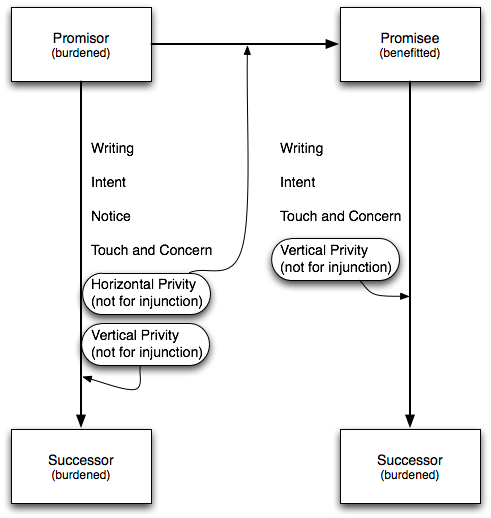

As with easements we look separately at whether the burden of a covenant runs with the burdened land and whether the benefit of a covenant runs with the benefitted land. For the burden of a real covenant to run, the following elements, which will be defined below, must be found: (1) writing, (2) intent, (3) notice, (4) horizontal privity, (5) vertical privity, and (6) touch and concern. The privity elements are not required for the burden of an equitable servitude to run. For the benefit of a real covenant to run, the following elements must be found: (1) writing, (2) intent, (3) vertical privity, and (4) touch and concern. Again, privity is not required to enforce an equitable servitude, so long as the plaintiff is an intended beneficiary of the covenant.

A successor of an owner of the servient, or burdened, land is only liable under a covenant if the burden runs to that owner. Likewise, the successor of an owner of the dominant, or benefitted, land may only enforce a covenant if the benefit of the covenant runs to that owner. These are two separate questions, and the running of the benefit and the running of the burden must be analyzed separately.

Writing

This seems like a straightforward requirement. As with easements, we do not require that every subsequent deed contain the covenant – only that the original covenant is in writing. Covenants may be included in original deeds of conveyance, or may be contained in separate agreements. They may also be contained in declarations, which are documents setting out covenants applicable to a whole subdivision rather than just individual parcels. The important thing here is that there is a writing. Whether that writing provides notice is a separate matter considered below.

Intent

Intent is not difficult to find. A covenant may use magic words – expressly declaring that it binds future owners or that it runs with the land – but will often be found to be intended to run with the land regardless. Most, but not all, courts will find intent to run where the touch and concern element is satisfied.

Notice

As with easements, notice can be either actual, inquiry, or record. And what is needed to show each is more or less identical to what is required there. Covenants contained in a declaration applicable to an entire subdivision are determined by some courts to constitute record notice even when the deeds of land in that subdivision do not reference the declaration. Other courts will insist on a reference to the declaration in a deed of the individual parcel itself before determining that the owner of that parcel had notice. The question comes down to whether a court (or legislature) believes it is reasonable to require title searchers to look for declarations, rather than just looking at the deeds of conveyance in the chain of title.

Horizontal Privity

This requirement measures the relationship between the two original contracting parties to a covenant. So if the covenant was executed in 1850, we care only about the relation between the parties that executed the agreement back in 1850, not about any subsequent owners. While the Third Restatement would do away with this requirement altogether, many states retain it. Note, though, that it is not required when seeking an injunction (i.e., enforcement of an equitable servitude).

The requirement can be satisfied in few ways. The original form of horizontal privity is known as tenurial privity and exists only when the parties are in a landlord-tenant relationship. Later, it was expanded to cover situations in which one party had an easement in the land of the other, called substituted privity. Together, these two kinds of privity are called mutual privity, which exists, more generally, when the parties have a simultaneous interest in the same parcel of land.

By far the most common way to find horizontal privity is also the most recent. Instantaneous privity is found when the covenant is created at the same time as a parcel is transferred. So, a covenant contained in a deed of sale will meet the horizontal privity requirement, as the covenant is created at the same instant as the parcel of land is deeded over.

There is no horizontal privity when neighbors simply come together and contract for restrictions. Suppose a group of neighbors is concerned about preserving trees and wants to impose reciprocal covenants on each of them not to cut trees unless certain conditions exist. They will not be in horizontal privity with one another, and therefore will not create a covenant enforceable by damages by simply contracting among themselves. They can get around this, however, by deeding over their properties to a third party who deeds the properties back with the covenants. This straw transaction creates horizontal privity.

Vertical Privity

Each of the above elements is purely formal. People who want to create a covenant that will run can do so by observing the requirements and executing the covenant so as to comply with them. Vertical privity, however, cannot be created where it does not exist. This requirement measures the relationship between an owner of land and his or predecessor in interest. So a real covenant may only be enforced, for damages, against an owner of burdened land if that owner is in vertical privity with a predecessor who was bound.

There are two kinds of vertical privity: relaxed and strict. Strict vertical privity between a predecessor and successor is found only if the predecessor retains no interest in the land. A landlord-tenant relationship fails this test, because the landlord retains an interest when he or she leases to a tenant. In a nutshell, sellers and buyers are generally in strict vertical privity but landlords and tenants are not.

Relaxed vertical privity is found between any two possessors. A neighbor of the owner of a piece of land is not in relaxed vertical privity with the predecessor of the owner. Also, an adverse possessor is usually deemed not to be in vertical privity with a predecessor.

Only relaxed vertical privity is required on the benefit side. Courts differ over which form is required on the burden side. The Third Restatement is a little more complex. It would eliminate the vertical privity requirement on the burden side of negative covenants but require strict vertical privity on the burden side of affirmative covenants. This means that the Restatement would not bind lessees with affirmative obligations, only with negative obligations. However, there is an escape hatch: the Third Restatement would require enforcement without strict vertical privity even of an affirmative covenant where the burden is “more reasonably performed” by the person in possession (i.e., the lessee).

Touch and Concern

This is the only requirement for a covenant to run with the land that looks at the substance of the covenant. Like strict vertical privity, it cannot be created if it does not exist. But further, it is a restriction on the kinds of covenants that will be deemed to run. There are at least three different kinds of tests for touch and concern. Only a brief outline will be given here, with further elaboration of the doctrine in the cases below.

First, under an older rule, courts will examine a covenant to see if provides physical benefits to the dominant holding and imposes physical burdens on the servient holding. This creates problem cases where it seems as though the obligations ought to run, and yet the physical nature of the covenant is difficult to discern. For example, a covenant to host a billboard on one’s land physically touches and concerns the burdened land but has no physical impact on any benefitted land. The obligation to pay money to keep up a communal gym or golf course does not seem to burden physically the land of the owner who is required to pay money.

Second, courts may ask whether the covenant between the parties benefits and burdens them “as landowners” rather than as individuals. This probably gets at whether the covenant provides benefits and imposes burdens that are location-specific, that are tied to the parties’ ownership of particular land, rather than burdens and benefits that would be unaffected if the parties lived elsewhere. Ask yourself whether the benefits of a covenant to an owner are greater because of where that owner lives. Similarly are the burdens related to ownership of land?

The Third Restatement and some courts would jettison the touch and concern requirement altogether in an effort to modernize the law of covenants. Instead, the analysis would focus on whether the covenant is unconscionable, a violation of public policy, and otherwise reasonable. When examining this approach, it is critical to remember that whether we think the contract between the original parties is violative of some important policies is a substantively different question from whether we think that contract should automatically bind successive landowners. We will discuss further, below, the difference between these questions.

Summary

Running of covenants is best appreciated in chart-form.

6.1. Formation

6.1.1. Written Covenants and Running with the Land

Davidson Bros., Inc. v. D. Katz & Sons, Inc.,

121 N.J. 196 (1990)

Sheppard A. Guryan argued the cause for appellant (Lasser, Hochman, Marcus, Guryan and Kuskin, attorneys; Bruce H. Snyder, on the brief).

Arthur L. Phillips argued the cause for respondent D. Katz & Sons, Inc., a New Jersey Corporation.

Linda K. Anderson, Assistant City Attorney, argued the cause for respondent City of New Brunswick, a Municipal Corporation (William J. Hamilton, Jr., City Attorney, attorney).

Mary M. Cheh argued the cause for respondent C-Town, a Division of Krasdale Foods, Inc., a New York Corporation (George J. Otlowski, Jr., attorney).

Robert J. Lecky argued the cause for respondent New Brunswick Housing Authority, a Body Corporate and Political (Stamberger & Lecky, attorneys).

The opinion of the Court was delivered by Garibaldi, J.

This case presents two issues. The first is whether a restrictive covenant in a deed, providing that the property shall not be used as a supermarket or grocery store, is enforceable against the original covenantor’s successor, a subsequent purchaser with actual notice of the covenant. The second is whether an alleged rent-free lease of lands by a public entity to a private corporation for use as a supermarket constitutes a gift of public property in violation of the New Jersey Constitution of 1947, article eight, section three, paragraphs two and three.

I

The facts are not in dispute. Prior to September 1980 plaintiff, Davidson Bros., Inc., along with Irisondra, Inc., a related corporation, owned certain premises located at 263-271 George Street and 30 Morris Street in New Brunswick (the “George Street” property). Plaintiff operated a supermarket on that property for approximately seven to eight months. The store operated at a loss allegedly because of competing business from plaintiff’s other store, located two miles away (the “Elizabeth Street” property). Consequently, plaintiff and Irisondra conveyed, by separate deeds, the George Street property to defendant D. Katz & Sons, Inc., with a restrictive covenant not to operate a supermarket on the premises. Specifically, each deed contained the following covenant:

The lands and premises described herein and conveyed hereby are conveyed subject to the restriction that said lands and premises shall not be used as and for a supermarket or grocery store of a supermarket type, however designated, for a period of forty (40) years from the date of this deed. This restriction shall be a covenant attached to and running with the lands.

The deeds were duly recorded in Middlesex County Clerk’s office on September 10, 1980. According to plaintiff’s complaint, its operation of both stores resulted in losses in both stores. Plaintiff alleges that after the closure of the George Street store, its Elizabeth Street store increased in sales by twenty percent and became profitable. Plaintiff held a leasehold interest in the Elizabeth Street property, which commenced in 1978 for a period of twenty years, plus two renewal terms of five years.

According to defendants New Brunswick Housing Authority (the “Authority”) and City of New Brunswick (the “City”), the closure of the George Street store did not benefit the residents of downtown New Brunswick. Defendants allege that many of the residents who lived two blocks away from the George Street store in multi-family and senior-citizen housing units were forced to take public transportation and taxis to the Elizabeth Street store because there were no other markets in downtown New Brunswick, save for two high-priced convenience stores.

The residents requested the aid of the City and the Authority in attracting a new food retailer to this urban-renewal area. For six years, those efforts were unsuccessful. Finally, in 1986, an executive of C-Town, a division of a supermarket chain, approached representatives of New Brunswick about securing financial help from the City to build a supermarket.

Despite its actual notice of the covenant the Authority, on October 23, 1986, purchased the George Street property from Katz for $450,000, and agreed to lease from Katz at an annual net rent of $19,800.00, the adjacent land at 263-265 George Street for use as a parking lot. The Authority invited proposals for the lease of the property to use as a supermarket. C-Town was the only party to submit a proposal at a public auction. The proposal provided for an aggregate rent of one dollar per year during the five-year lease term with an agreement to make $10,000 in improvements to the exterior of the building and land. The Authority accepted the proposal in 1987. All the defendants in this case had actual notice of the restrictions contained in the deed and of plaintiff’s intent to enforce the same. Not only were the deeds recorded but the contract of sale between Katz and the Housing Authority specifically referred to the restrictive covenant and the pending action.

Plaintiff filed this action in the Chancery Division against defendants D. Katz & Sons, Inc., the City of New Brunswick, and C-Town. The first count of the complaint requested a declaratory judgment that the noncompetition covenant was binding on all subsequent owners of the George Street property. The second count requested an injunction against defendant City of New Brunswick from leasing the George Street property on any basis that would constitute a gift to a private party in violation of the state constitution. Both counts sought compensatory and punitive damages. That complaint was then amended to include defendant the New Brunswick Housing Authority.

[The trial court denied plaintiff’s motion for summary judgment, and the Appellate Division affirmed.]

II

A. Genesis and Development of Covenants Regarding the Use of Property

Covenants regarding property uses have historical roots in the courts of both law and equity. The English common-law courts first dealt with the issue in Spencer’s Case, 5 Co. 16a, 77 Eng.Rep. 72 (Q.B. 1583). The court established two criteria for the enforcement of covenants against successors. First, the original covenanting parties must intend that the covenant run with the land. Second, the covenant must “touch and concern” the land. Id. at 16b, 77 Eng.Rep. at 74. The court explained the concept of “touch and concern” in this manner:

But although the covenant be for him [an original party to the promise] and his assigns, yet if the thing to be done be merely collateral to the land, and doth not touch and concern the thing demised in any sort, there the assignee shall not be charged. As if the lessee covenants for him and his assignees to build a house upon the land of the lessor which is no parcel of the demise, or to pay any collateral sum to the lessor, or to a stranger, it shall not bind the assignee, because it is merely collateral, and in no manner touches or concerns the thing that was demised, or that is assigned over, and therefore in such case the assignee of the thing demised cannot be charged with it, no more than any other stranger. [Ibid.]

The English common-law courts also developed additional requirements of horizontal privity (succession of estate), vertical privity (a landlord-tenant relationship), and that the covenant have “proper form,” in order for the covenant to run with the land. C. Clark, Real Covenants and Other Interests Which Run With the Land 94, 95 (2d ed. 1947) (Real Covenants). Those technical requirements made it difficult, if not impossible, to protect property through the creation of real covenants. Commentary, “Real Covenants in Restraint of Trade – When Do They Run With the Land?,” 20 Ala.L.Rev. 114, 115 (1967).

To mitigate and to eliminate many of the formalities and privity rules formulated by the common-law courts, the English chancery courts in Tulk v. Moxhay, 2 Phil. 774, 41 Eng.Rep. 1143 (Ch. 1848), created the doctrine of equitable servitudes. In Tulk, land was conveyed subject to an agreement that it would be kept open and maintained for park use. A subsequent grantee, with notice of the restriction, acquired the park. The court held that it would be unfair for the original covenantor to rid himself of the burden to maintain the park by simply selling the land. In enjoining the new owner from violating the agreement, the court stated:

It is said that, the covenant being one which does not run with the land, this court cannot enforce it, but the question is, not whether the covenant runs with the land, but whether a party shall be permitted to use the land in a manner inconsistent with the contract entered into by his vendor, and with notice of which he purchased. Of course, the price would be affected by the covenant, and nothing could be more inequitable than that the original purchaser should be able to sell the property the next day for a greater price, in consideration of the assignee being allowed to escape from the liability which he had himself undertaken.

[Id. at 777-78, 41 Eng.Rep. 1144].

The court thus enforced the covenant on the basis that the successor had purchased the property with notice of the restriction. Adequate notice obliterated any express requirement of “touch and concern.” Reichman, “Toward a Unified Concept of Servitudes,” 55 S.Cal.L.Rev. 1177, 1225 (1982); French, “Toward a Modern Law of Servitudes: Reweaving Ancient Strands,” 55 S.Cal.L.Rev. 1261, 1276-77 (1982). But see Burger, “A Policy Analysis of Promises Respecting the Use of Land,” 55 Minn.L.Rev. 167, 217 (1970) (focusing on language in Tulk that refers to “use of land” and “attached to property” as implied recognition of “touch and concern” rule).

Some early commentators theorized that the omission of the technical elements of property law such as the “touch and concern” requirement indicated that Tulk was based on a contractual as opposed to a property theory. C. Clark, supra, Real Covenants, at 171-72 nn. 3 and 4; 3 H. Tiffany, Real Property § 861, at 489 (3d ed. 1939); Ames, “Specific Performance For and Against Strangers to Contract,” 17 Harv.L.Rev. 174, 177-79 (1904); Stone, “The Equitable Rights and Liabilities of Strangers to the Contract,” 18 Colum.L.Rev. 291, 294-95 (1918). Others contend that “touch and concern” is always, at the very least, an implicit element in any analysis regarding enforcement of covenants because “any restrictive easement necessitates some relation between the restriction and the land itself.” McLoone, “Equitable Servitudes – A Recent Case and Its Implications for the Enforcement of Covenants Not to Compete,” 9 Ariz.L.Rev. 441, 444, 447 n. 5 (1968). Still others explain the “touch and concern” omission on the theory that equitable servitudes usually involve negative covenants or promises on how the land should not be used. Thus, because those covenants typically do touch and concern the land, the equity courts did not feel the necessity to state “touch and concern” as a separate requirement. Berger, “Integration of the Law of Easements, Real Covenants and Equitable Servitudes,” 43 Wash. & Lee L.Rev., 337, 362 (1986). Whatever the explanation, the law of equitable servitudes did generally continue to diminish or omit the “touch and concern” requirement.

B. New Jersey’s treatment of noncompetitive covenants restraining the use of property

Our inquiry of New Jersey law on restrictive property use covenants commences with a re-examination of the rule set forth in Brewer v. Marshall & Cheeseman, supra, 19 N.J. Eq. at 537, that a covenant will not run with the land unless it affects the physical use of the land. Hence, the burden side of a noncompetition covenant is personal to the covenantor and is, therefore, not enforceable against a purchaser. In Brewer v. Marshall & Cheeseman, the court objected to all noncompetition covenants on the basis of public policy and refused to consider them in the context of the doctrine of equitable servitudes. Similarly, in National Union Bank at Dover v. Segur, 39 N.J.L. 173 (Sup.Ct. 1877), the court held that only the benefit of a noncompetition covenant would run with the land, but the burden would be personal to the covenantor. See 5 R. Powell, supra, § 675[3] at 60-109. Because the burden of a noncompetition covenant is deemed to be personal in these cases, enforcement would be possible only against the original covenantor. As soon as the covenantor sold the property, the burden would cease to exist.

Brewer and National Union Bank have been subsequently interpreted as embodying the “unnecessarily strict” position that “while the benefit of [a noncompetition covenant] will run with the land, the burden of the covenant is necessarily personal to the covenantor.” 5 Powell, supra, § 675[3] at 60-109. This blanket prohibition of noncompetition covenants has been ignored in more recent decisions that have allowed the burden of a noncompetition covenant to run, see Renee Cleaners Inc. v. Good Deal Supermarkets of N.J., 89 N.J. Super. 186, 214 A.2d 437 (App.Div. 1965) (enforcing at law covenant not to lease property for dry-cleaning business as against subsequent purchaser of land); Alexander’s v. Arnold Constable Corp., 105 N.J. Super. 14, 28, 250 A.2d 792 (Ch. 1969) (enforcing promise entered into by prior holders of land not to operate department store as against current landowner). Nonetheless, Brewer may still retain some vitality, as evidenced by the trial court’s reliance on it in this case.

The per se prohibition that noncompetition covenants regarding the use of property do not run with the land is not supported by modern real-covenant law, and indeed, appears to have support only in the Restatement of Property section on the running of real covenants, § 537 comment f. 5 Powell, supra, at § 675[3] at 60-109. Specifically, that approach is rejected in the Restatement’s section on equitable servitudes, see Restatement of Property, § 539 comment k (1944); see also Whitinsville Plaza, Inc. v. Kotseas, 378 Mass. 85, 95-96, 390 N.E.2d 243, 249 (1979) (overruling similarly strict approach inasmuch as it was “anachronistic” compared to modern judicial analysis of noncompetition covenants, which focuses on effects of covenant).

Commentators also consider the Brewer rule an anachronism and in need of change, as do we. 5 Powell, supra, ¶ 678 at 192. Accordingly, to the extent that Brewer holds that a noncompetition covenant will not run with the land, it is overruled.

Plaintiff also argues that the “touch and concern” test likewise should be eliminated in determining the enforceability of fully negotiated contracts, in favor of a simpler “reasonableness” standard that has been adopted in most jurisdictions. That argument has some support from commentators, see, e.g., Epstein, “Notice and Freedom of Contract in the Law of Servitudes,” 55 S.Cal.L.Rev. 1353, 1359-61 (1982) (contending that “touch and concern” complicates the basic analysis and limits the effectiveness of law of servitudes), including a reporter for the Restatement (Third) of Property, see French, “Servitudes Reform and the New Restatement of Property: Creation Doctrines and Structural Simplification,” 73 Cornell L.Rev. 928, 939 (1988) (arguing that “touch and concern” rule should be completely eliminated and that the law should instead directly tackle the “running” issue on public-policy grounds).

New Jersey courts, however, continue to focus on the “touch and concern” requirement as the pivotal inquiry in ascertaining whether a covenant runs with the land. Under New Jersey law, a covenant that “exercise[s] [a] direct influence on the occupation, use or enjoyment of the premises” satisfies the “touch and concern” rule. Caullett v. Stanley Stilwell & Sons, Inc., 67 N.J. Super. 111, 116, 170 A.2d 52 (App.Div. 1961). The covenant must touch and concern both the burdened and the benefitted property in order to run with the land. Ibid; Hayes v. Waverly & Passaic R.R., 51 N.J. Eq. 3, 27 A. 648 (Ch. 1893). Because the law frowns on the placing of restrictions on the freedom of alienation of land, New Jersey courts will enforce a covenant only if it produces a countervailing benefit to justify the burden. Restatement of Property § 543, comment c (1944); Reichman, supra, 55 S.Cal.L.Rev. at 1229.

Unlike New Jersey, which has continued to rely on the “touch and concern” requirement, most other jurisdictions have omitted “touch and concern” from their analysis and have focused instead on whether the covenant is reasonable. [A long list of citations is omitted.]

Even the majority of courts that have retained the “touch and concern” test have found that noncompetition covenants meet the test’s requirements. See, e.g., Dick v. Sears-Roebuck & Co., 115 Conn. 122, 160 A. 432 (1932) (holding “touch and concern” element satisfied where noncompetition covenants restrained “use to which the land may be put in the future as well as in the present, and which might very likely affect its value”); Singer v. Wong, 35 Conn. Supp. 640, 404 A.2d 124 (1978) (restrictive covenant in deed providing that premises not be used as shopping center “touched and concerned” land because it materially affected value of land) [other cases omitted].

The “touch and concern” test has, thus, ceased to be, in most jurisdictions, intricate and confounding. Courts have decided as an initial matter that covenants not to compete do touch and concern the land. The courts then have examined explicitly the more important question of whether covenants are reasonable enough to warrant enforcement. The time has come to cut the gordian knot that binds this state’s jurisprudence regarding covenants running with the land. Rigid adherence to the “touch and concern” test as a means of determining the enforceability of a restrictive covenant is not warranted. Reasonableness, not esoteric concepts of property law, should be the guiding inquiry into the validity of covenants at law. We do not abandon the “touch and concern” test, but rather hold that the test is but one of the factors a court should consider in determining the reasonableness of the covenant.

A “reasonableness” test allows a court to consider the enforceability of a covenant in view of the realities of today’s commercial world and not in the light of outmoded theories developed in a vastly different commercial environment. Originally strict adherence to “touch and concern” rule in the old English common-law cases and in Brewer, was to effectuate the then pervasive public policy of restricting many, if not all, encumbrances of the land. Courts today recognize that it is not unreasonable for parties in commercial-property transactions to protect themselves from competition by executing noncompetition covenants. Businesspersons, either as lessees or purchasers may be hesitant to invest substantial sums if they have no minimal protection from a competitor starting a business in the near vicinity. Hence, rather than limiting trade, in some instances, restrictive covenants may increase business activity.

We recognize that “reasonableness” is necessarily a fact sensitive issue involving an inquiry into present business conditions and other factors specific to the covenant at issue. Nonetheless, as do most of the jurisdictions, we find that it is a better test for governing commercial transactions than are obscure anachronisms that have little meaning in today’s commercial world. The pivotal inquiry, therefore, becomes what factors should a court consider in determining whether such a covenant is “reasonable” and hence enforceable. We conclude that the following factors should be considered:

- The intention of the parties when the covenant was executed, and whether the parties had a viable purpose which did not at the time interfere with existing commercial laws, such as antitrust laws, or public policy.

- Whether the covenant had an impact on the considerations exchanged when the covenant was originally executed. This may provide a measure of the value to the parties of the covenant at the time.

- Whether the covenant clearly and expressly sets forth the restrictions.

- Whether the covenant was in writing, recorded, and if so, whether the subsequent grantee had actual notice of the covenant.

- Whether the covenant is reasonable concerning area, time or duration. Covenants that extend for perpetuity or beyond the terms of a lease may often be unreasonable. Alexander’s v. Arnold Constable, 105 N.J. Super. 14, 27, 250 A.2d 792 (Ch.Div. 1969); Cragmere Holding Corp. v. Socony Mobile Oil Co., 65 N.J. Super. 322, 167 A.2d 825 (App.Div. 1961).

- Whether the covenant imposes an unreasonable restraint on trade or secures a monopoly for the covenantor. This may be the case in areas where there is limited space available to conduct certain business activities and a covenant not to compete burdens all or most available locales to prevent them from competing in such an activity. Doo v. Packwood, 265 Cal. App.2d 752, 71 Cal. Rptr. 477 (1968); Kettle River R. v. Eastern Ry. Co., 41 Minn. 461, 43 N.W. 469 (1889).

- Whether the covenant interferes with the public interest. Natural Prods. Co. v. Dolese & Shepard Co., 309 Ill. 230, 140 N.E. 840 (1923).

- Whether, even if the covenant was reasonable at the time it was executed, “changed circumstances” now make the covenant unreasonable. Welitoff v. Kohl, 105 N.J. Eq. 181, 147 A. 390 (1929).

In applying the “reasonableness” factors, trial courts may find useful the analogous standards we have adopted in determining the validity of employee covenants not to compete after termination of employment. Although enforcement of such a covenant is somewhat restricted because of countervailing policy considerations, we generally enforce an employee non-competition covenant as reasonable if it “simply protects the legitimate interests of the employer imposes no undue hardship on the employee, and is not injurious to the public.” Solari Indus. v. Malady, 55 N.J. 571, 576, 264 A.2d 53 (1970). We also held in Solari that if such a covenant is found to be overbroad, it may be partially enforced to the extent reasonable under the circumstances. Id. at 585, 264 A.2d 53. That approach to the enforcement of restrictive covenants in deeds offers a mechanism for recognizing and balancing the legitimate concerns of the grantor, the successors in interest, and the public.

The concurrence maintains that the initial validity of the covenant is a question of contract law while its subsequent enforceability is one of property law. Post at 221, 579 A.2d at 300. The result is that the concurrence uses reasonableness factors in construing the validity of the covenant between the original covenantors, but as to successors-in-interest, claims to adhere strictly to a “touch and concern” test. Post at 222, 579 A.2d at 301. Such strict adherence to a “touch and concern” analysis turns a blind eye to whether a covenant has become unreasonable over time. Indeed many past illogical and contorted applications of the “touch and concern” rules have resulted because courts have been pressed to twist the rules of “touch and concern” in order to achieve a result that comports with public policy and a free market. Most jurisdictions acknowledge the reasonableness factors that affect enforcement of a covenant concerning successors-in-interest, instead of engaging in the subterfuge of twisting the touch and concern test to meet the required result. New Jersey should not remain part of the small minority of States that cling to an anachronistic rule of law. Supra at 210, 579 A.2d at 295.

There is insufficient evidence in this record to determine whether the covenant is reasonable. Nevertheless, we think it instructive to comment briefly on the application of the “reasonableness” factors to this covenant. We consider first the intent of the parties when the covenant was executed. It is undisputed that when plaintiff conveyed the property to Katz, it intended that the George Street store would not be used as a supermarket or grocery store for a period of forty years to protect his existing business at the Elizabeth Street store from competition. Plaintiff alleges that the purchase price negotiated between it and Katz took into account the value of the restrictive covenant and that Katz paid less for the property because of the restriction. There is no evidence, however, of the purchase price. It is also undisputed that the covenant was expressly set forth in a recorded deed, that the Authority took title to the premises with actual notice of the restrictive covenant, and, indeed, that all the defendants, including C-Town, had actual notice of the covenant.

The parties do not specifically contest the reasonableness of either the duration or area of the covenant. Aspects of the “touch and concern” test also remain useful in evaluating the reasonableness of a covenant, insofar as it aids the courts in differentiating between promises that were intended to bind only the individual parties to a land conveyance and promises affecting the use and value of the land that was intended to be passed on to subsequent parties. Covenants not to compete typically do touch and concern the land. In noncompetition cases, the “burden” factor of the “touch and concern” test is easily satisfied regardless of the definition chosen because the covenant restricts the actual use of the land. Berger, supra, 52 Wash.L.Rev. at 872. The Appellate Division properly concluded that the George Street store was burdened. However, we disagree with the Appellate Division’s conclusion that in view of the covenant’s speculative impact, the covenant did not provide a sufficient “benefit” to the Elizabeth Street property because it burdened only a small portion (George Street store) of the “market circle” (less than one-half acre in a market circle of 2000 acres).

The size of the burdened property relative to the market area is not a probative measure of whether the Elizabeth store was benefitted. Presumably, the use of the Elizabeth Street store as a supermarket would be enhanced if competition were lessened in its market area. If plaintiff’s allegations that the profits of the Elizabeth Street store increased after the sale of the George Street store are true, this would be evidence that a benefit was “conveyed” on the Elizabeth Street store. Likewise, information that the area was so densely populated, that the George Street property was the only unique property available for a supermarket, would show that the Elizabeth Street store property was benefitted by the covenant. In this connection the C-Town executive in his deposition noted that the George Street store location “businesswise was promising because there’s no other store in town.” Such evidence, however, also should be considered in determining the “reasonableness” of the area covered by the covenant and whether the covenant unduly restrained trade.

Defendants’ primary contention is that due to the circumstances of the neighborhood and more particularly the circumstances of the people of the neighborhood, plaintiff’s covenant interferes with the public’s interest. Whether that claim is essentially that the community has changed since the covenant was enacted or that the circumstances were such that when the covenant was enacted, it interfered with the public interest, we are unable to ascertain from the record. “Public interest” and “changed circumstances” arguments are extremely fact-sensitive. The only evidence that addresses those issues, the three affidavits of Mr. Keefe, Mr. Nero and Ms. Scott, are insufficient to support any finding with respect to those arguments.

The fact-sensitive nature of a “reasonableness” analysis make resolution of this dispute through summary judgment inappropriate. We therefore remand the case to the trial court for a thorough analysis of the “reasonableness” factors delineated herein.

The trial court must first determine whether the covenant was reasonable at the time it was enacted. If it was reasonable then, but now adversely affects commercial development and the public welfare of the people of New Brunswick, the trial court may consider whether allowing damages for breach of the covenant is an appropriate remedy. C-Town could then continue to operate but Davidson would get damages for the value of his covenant. On the limited record before us, however, it is impossible to make a determination concerning either reasonableness of the covenant or whether damages, injunctive relief, or any relief is appropriate.

In sum, we reject the trial court’s conclusion because it depends largely on the continued vitality of Brewer, which we hereby overrule. Supra at 201-202, 579 A.2d at 290-291. Likewise, we reject the Appellate Division’s reliance on the “touch and concern” test. Instead, the proper test to determine the enforceability of a restricted noncompetition covenant in a commercial land transaction is a test of “reasonableness,” an approach adopted by a majority of the jurisdictions.

III

The other issue before us concerns whether the lease granted by the Housing Authority to C-Town constitutes an impermissible gift of public property in violation of the State Constitution.

… .

We remand to the trial court to determine whether the purchase, lease, and operation of the supermarket constituted a public purpose, and, if so, whether the Housing Authority used justifiable means to attract a supermarket to the area of downtown New Brunswick.

Judgment reversed and cause remanded for further proceedings consistent with this opinion.

Pollock, J., concurring.

The Court reverses the Appellate Division’s affirmance of the Chancery Division’s grant of summary judgment invalidating the restrictive covenant and remands the matter to the Chancery Division for a plenary hearing. Although I concur in the judgment of remand, I believe it should be on different terms.

My basic difference with the majority is that I believe the critical consideration in determining the validity of this covenant is whether it is reasonable as to scope and duration, a point that has never been at issue in this case. Nor has there ever been any question whether the original parties to the covenant, Davidson Bros., Inc. (Davidson), and D. Katz & Sons, Inc. (Katz) intended that the covenant should run with the land. Likewise, the New Brunswick Housing Authority (the Authority) and C-Town have never disputed that they did not have actual notice of the covenant or that there was privity between them and Katz. Finally, the defendants have not contended that the covenant constitutes an unreasonable restraint on trade or that it has an otherwise unlawful purpose, such as invidious discrimination. Davidson, moreover, makes the uncontradicted assertion that the covenant is a burden to the George Street property and benefits the Elizabeth Street property. Hence, the covenant satisfies the requirement that it touch and concern the benefitted and burdened properties.

The fundamental flaw in the majority’s analysis is in positing that an otherwise-valid covenant can become invalid not because it results in an unreasonable restraint on trade, but because invalidation facilitates a goal that the majority deems worthy. Considerations such as “changed circumstances” and “the public interest,” when they do not constitute such a restraint, should not affect the enforceability of a covenant. Instead, they should relate to whether the appropriate method of enforcement is an injunction or damages. A court should not declare a noncompetition covenant invalid merely because enforcement would lead to a result with which the court disagrees. This leads me to conclude that the only issue on remand should be whether the appropriate remedy is damages or an injunction.

Enforcement of the restriction by an injunction will deprive the downtown residents of the convenience of shopping at the George Street property. Refusal to enforce the covenant, on the other hand, will deprive Davidson of the benefit of its covenant. Thus, the case presents a tension between two worthy objectives: the continued operation of the supermarket for the benefit of needy citizens, and the enforcement of the covenant. An award of damages to Davidson rather than the grant of an injunction would permit the realization of both objectives.

-I-

I begin by questioning the majority’s formulation and application of a reasonableness test for determining whether the covenant runs with the land. The law has long distinguished between the validity of a covenant between original-contracting parties from the enforceability of a covenant against the covenantor’s successor-in-interest. Initial validity is a question of contract law; enforceability against subsequent parties is one of property law. Caullett v. Stanley Stilwell & Sons, 67 N.J. Super. 111, 116, 170 A.2d 52 (App.Div. 1961); R. Cunningham, W. Stoebuck, and D. Whitman, The Law of Property 467 (1984) (Cunningham). That distinction need not foreclose a subsequent owner of the burdened property from challenging the validity of the contract between the original parties. The distinction, however, sharpens the analysis of the effect of the covenant.

In this case, the basic issue is enforceability of the covenant against the Authority and C-Town, successors in interest to Katz. Thus, the only relevant consideration is whether the covenant “touches and concerns” the benefitted and burdened properties. For the Chancery Division, the critical issue was “whether the restriction burdens the land in the hands of the Authority.” As the majority points out, “[i]n contrast to the trial court’s decision, the Appellate Division’s rationale was premised on the failure of the benefit of the covenant to run, not of the burden.” Ante at 202, 579 A.2d at 291. The majority correctly disagrees with the Appellate Division’s rationale, properly observing that a covenant can provide a benefit even without burdening most of the properties in the relevant market area. Ante at 214, 579 A.2d at 297. Concerning the running of the burden on the George Street property, the majority views Brewer v. Marshall & Cheeseman, 19 N.J. Eq. 537 (E. & A. 1868), as an anachronism. It properly overrules the holding of Brewer “that a noncompetition covenant will not run with the land * * *.” Ante at 207, 579 A.2d at 293. Continuing, the majority observes that in most jurisdictions the “‘touch and concern’ test has * * * ceased to be * * * intricate and confounding,” and that “[c]ourts have decided as an initial matter that covenants not to compete do touch and concern the land.” Ante at 209, 579 A.2d at 294. Instead of concluding its analysis, the majority adds: “We do not abandon the ‘touch and concern’ test, but rather hold that the test is but one of the factors a court should consider in determining the reasonableness of the covenant.” Ante at 210, 579 A.2d at 295.

The Court can decide the present case without introducing a new test. On the present record, no question exists about the running of the benefit of the covenant. First, the party seeking to enforce the covenant is Davidson, the original leaseholder, not a successor in interest, of the Elizabeth Street property. Second, as the language of the covenant indicates, the original contracting parties, Davidson and Katz, indicated that the covenant would run with the land. Third, Davidson makes the uncontradicted assertions that both stores were unprofitable before the sale, that the Elizabeth Street store after the sale of the George Street property enjoyed a twenty-per-cent sales increase, and that the reopening of the George Street property caused it to suffer a loss of income. Finally, as the majority recognizes, the lower courts erred in concluding that the covenant did not “touch and concern” the burdened and benefitted properties. Ante at 213, 579 A.2d at 296.

It is virtually inconceivable that the covenant does not benefit the Elizabeth Street property. New Jersey courts have declared variously that the benefit “must exercise direct influence upon the occupation, use or enjoyment of the premises,” Caullett, supra, 67 N.J. Super. at 116, 170 A.2d 52, and that the covenant must confer “a direct benefit on the owner of land by reason of his ownership,” National Union Bank at Dover v. Segur, 39 N.J.L. 173, 186 (Sup.Ct. 1877). Scholars have written that a covenant’s benefit touches and concerns land if it renders the owner’s interest in the land more valuable, Bigelow, The Content of Covenants in Leases, 12 Mich.L.Rev. 639, 645 (1914), or if “the parties as laymen and not as lawyers” would naturally view the covenant as one that aids “the promisee as landowner,” C. Clark, Real Covenants and Other Interests Which Run with the Land 99 (2d ed. 1947) (Clark); see also 5 R. Powell & P. Rohan, Powell on Real Property ¶ 673[2][a] (1990) (Powell) (inclining towards Clark’s view). Like most courts, leading scholars, Powell, supra, § 675[3]; Cunningham, supra, at 474-75; and Clark, supra, at 106, believe that under the “touch and concern” test, the benefit of non-competition covenants should run with the land.

The conclusion that this covenant “touches and concerns” the land should end the inquiry about enforceability against the Authority and C-Town. The majority, however, holds that the “touch and concern” test is “but one of the factors a court should consider in determining the reasonableness of the covenant.” Ante at 210, 579 A.2d at 295. The majority’s inquiry about reasonableness, however, confuses the issue of validity of the original contract between Davidson and Katz with enforceability against the subsequent owner, the Authority. This confusion of validity with enforceability threatens to add uncertainty to an already troubled area of the law. As explained by one leading authority, “[t]he judicial reaction to this confusion [in the law of covenants and equitable servitudes] has often been to state the law so as to achieve the desired result in a particular case. Obviously, this has caused frequent misstatements of the law, which has deepened the overall confusion.” Powell, supra, ¶ 670[2].

The majority inaccurately asserts, ante at 208, 579 A.2d at 294, that most jurisdictions “have focused on whether the covenant is reasonable enough to warrant enforcement.” Not one case cited by the majority has concluded that a covenant that is reasonable against the original covenantor would be unreasonable against the covenantor’s successor who takes with notice. For example, in Hercules Powder Co. v. Continental Can Co., 196 Va. 935, 945, 86 S.E.2d 128, 133 (1955), only after first concluding that the restriction was reasonable did the court consider “whether it is enforceable by Continental Can, an assignee of the original covenantee, against Hercules, an assignee of the original covenantor.” In determining that Hercules was subject to the restriction, the court considered only whether it purchased the land with notice of the restriction. Id. at 946-48, 86 S.E.2d at 134-35. Similarly, in Quadro Stations v. Gilley, 7 N.C. App. 227, 234, 172 S.E.2d 237, 242 (1970), the court first concluded that the restriction was valid, and then held that it was enforceable against defendants, successors in interest to the original covenanting parties. Nothing in the opinion implies that a restriction that was reasonable between the original parties would be unenforceable against a purchaser of the burdened property who bought with notice. Doo v. Packwood, 265 Cal. App.2d 752, 756, 71 Cal. Rptr. 477, 481 (1968), is likewise unavailing to the majority. There, when purchasing a lot on which Doo had operated a grocery store, Packwood agreed to a noncompetition covenant. After concluding that the covenant was reasonable as between the original parties, the court found that it would be binding on a future purchaser with notice. Ibid. In effect, future purchasers would be bound so long as Doo continued to operate a competitive grocery store. Ibid. To conclude, the cited cases hold that a reasonable noncompetition covenant binding on the original covenantor likewise binds a subsequent purchaser with notice. Hence, the majority misperceives the focus of the out-of-state cases. The result is that the majority’s reasonableness test introduces unnecessary uncertainty in the analysis of covenants running with the land.

As troublesome as uncertainty is in other areas of the law, it is particularly vexatious in the law of real property. The need for certainty in conveyancing, like that in estate planning, is necessary for people to structure their affairs. Covenants that run with the land can affect the value of real property not only at the time of sale, but for many years thereafter. Consequently, vendors and purchasers, as well as their successors, need to know whether a covenant will run with the land. The majority acknowledges that noncompetition covenants play a positive role in commercial development. Ante at 210, 579 A.2d at 295. Notwithstanding that acknowledgement, the majority’s reasonableness test generates confusion that threatens the ability of commercial parties and their lawyers to determine the validity of such covenants. This, in turn, impairs the utility of noncompetition covenants in real estate transactions.

As between the vendor and purchaser, a noncompetition covenant generally should be treated as valid if it is reasonable in scope and duration, Irving Inv. Corp. v. Gordon, 3 N.J. 217, 221, 69 A.2d 725 (1949); Heuer v. Rubin, 1 N.J. 251, 256-57, 62 A.2d 812 (1949); Scherman v. Stern, 93 N.J. Eq. 626, 630, 117 A. 631 (E. & A. 1922), and neither an unreasonable restraint on trade nor otherwise contrary to public policy. A covenant would contravene public policy if, for example, its purpose were to secure a monopoly, Quadro Stations, supra, 7 N.C. App. at 235, 172 S.E.2d at 242; Hercules Powder Co., supra, 196 Va. at 944-45, 86 S.E.2d at 132-33, or to carry out an illegal object, such as invidious discrimination, see, e.g., N.J.S.A. 46:3-23 (declaring restrictive covenants in real estate transactions void if based on race, creed, color, national origin, ancestry, marital status, or sex).

Applying those principles to the validity of the agreement between Davidson and Katz, I find this covenant enforceable against defendants. The majority acknowledges that “[t]he parties do not specifically contest the reasonableness of either the duration or the area of the covenant.” Ante at 213, 579 A.2d at 296. I agree. The covenant is limited to one parcel, the George Street property. Defendants do not assert that Davidson has restricted or even owns other property in New Brunswick. Furthermore, they do not allege that other property is not available for a supermarket. In brief, the Authority has not alleged that at the time of the sale from Davidson to Katz, or even at present, the George Street property was the only possible site in New Brunswick for a supermarket. Consequently, the covenant may not be construed to give rise to a monopoly. In all of New Brunswick it restricts a solitary one-half acre tract from use for a single purpose. Indeed, the record demonstrates that the Authority explored other options, including expansion of a food cooperative and increasing the product lines at nearby convenience stores. Nothing in the record supports the conclusion that the covenant might be unreasonable respecting space.

Nor does anything indicate that the forty-year length of the restriction between Davidson and Katz is unreasonable in time. As we have stated, “where the space contained in the covenant is reasonable and proper there need be no limitation as to time.” Rubin, supra, 1 N.J. at 256-57, 62 A.2d 812. That statement echoes the words “certainly it is no objection to an agreement not to compete with a mercantile business that the restraint is unlimited in point of time when [as here] it is reasonably limited in point of space.” Stern, supra, 93 N.J. Eq. at 630, 117 A. 631. To sustain the subject covenant we need not go so far as to say that a covenant could never be unreasonably long. In an appropriate case, a court, drawing on the analogy to restrictive covenants in employment contracts, might reform a covenant so that it lasts only for a reasonable time. Solari Indus. v. Malady, 55 N.J. 571, 264 A.2d 53 (1970). This is not such a case.

Here, Davidson holds a lease on the Elizabeth Street property for a term of twenty years, with two renewable five-year terms. Those lease terms are substantially, if not precisely, coextensive with the term of the covenant. If, on remand, the Chancery Division should find that the additional ten-year period is not enforceable by Davidson, it should also find that the restriction is valid for the thirty-year period during which Davidson’s lease may run. In sum, I believe that the covenant is reasonable at least for the term of Davidson’s lease.

To the extent that noncompetition covenants in real estate transactions are deemed valid if reasonable in scope and duration, they are more readily upheld than similar covenants arising out of employment contracts. Solari Indus., supra, 55 N.J. at 576, 264 A.2d 53. In this regard, Williston points out that “[r]estriction upon the use of real property is considered less likely to affect the public interest adversely than restraint of the activities of individual parties and accordingly, such covenants are usually held not contrary to public policy.” 14 Williston on Contracts § 1642 (3d ed. 1972) (Williston). Nothing in the record supports the conclusion that when made or at present the subject covenant was an unreasonable restraint on trade or otherwise contrary to public policy.

Certain of the factors identified by the majority must be present for a covenant to run apart from the considerations of reasonableness. Such factors are the intent of the parties that the covenant run, clarity of the express restrictions, whether the covenant was in writing, and whether it was recorded. Caullett, supra, 67 N.J. Super. at 116, 170 A.2d 52; Petersen v. Beekmere, 117 N.J. Super. 155, 166-67, 283 A.2d 911 (Ch.Div. 1971); Clark, supra, at 94; Cunningham, supra, at 470. As previously indicated, all those factors are present in this case. If they had not been present, the covenant would have been unenforceable without reference to a reasonableness test. Duplicating those factors in such a test is counterproductive.

The majority’s three remaining factors also pose troubling problems. Without citing any authority, the majority invites review of “[w]hether the covenant had an impact on the considerations exchanged when the covenant was originally executed.” Ante at 210, 579 A.2d at 295. As the majority acknowledges, however, Davidson has made the uncontradicted assertion “that the purchase price negotiated between it and Katz took into account the value of the restrictive covenant and that Katz paid less for the property because of the restriction.” Ante at 213, 579 A.2d at 296.

In contract matters, courts ordinarily concern themselves with the existence, not the adequacy, of consideration. Kampf v. Franklin Life Ins. Co., 33 N.J. 36, 43, 161 A.2d 717 (1960). Because a noncompetition covenant in a commercial-real-estate sale involves the sale of property in exchange for the payment of the purchase price and the noncompetition covenant, it would be difficult to argue that the covenant was not supported by consideration. In fact, the majority does not cite to a single case in which a noncompetition covenant in a real-estate transaction has been declared invalid for lack of consideration.

Recognizing that the covenant should run is consistent with the intent of the contracting parties and reflects the economic consequences of their transaction. As Chief Justice Beasley wrote in National Union Bank at Dover, supra, 39 N.J.L. at 187, “[s]ince these parties most manifestly have thought that the stipulation in question gave additional value to the property, why, and on what ground, should the court declare that such was not the case?” See DeGray v. Monmouth Beach Club House Co., 50 N.J. Eq. 329, 333, 24 A. 388 (Ch. 1892) (“The equity thus enforced arises from the inference that the covenant has, to a material extent, entered into the consideration of the purchase, and that it would be unjust to the original grantor to permit the covenant to be violated.”); Tulk v. Moxhay, 2 Phil. 774, 777-78, 41 Eng.Rep. 1143, 1144 (1848) (“Of course, the price would be affected by the covenant and nothing could be more inequitable than that the original purchaser should be able to sell the property the next day for a greater price, in consideration of the assignee being allowed to escape from the liability which he had himself undertaken.”).

The majority’s other two factors are “whether the covenant interferes with the public interest,” and “whether, even if the covenant was reasonable at the time it was executed, ‘changed circumstances’ now make the covenant unreasonable.” Ante at 212, 579 A.2d at 295. In this regard, the majority adds that

[t]he trial court must first determine whether the covenant was reasonable at the time it was enacted. If it was reasonable then, but now adversely affects commercial development and the public welfare of the people of New Brunswick, the trial court may consider whether allowing damages is an appropriate remedy. C-Town could continue to operate but Davidson would get damages for the value of his [sic] covenant. On the limited record before us, however, it is impossible to make a determination as to the reasonableness of the covenant or whether damages, injunctive relief, or any relief is appropriate. [Ante at 215, 579 A.2d at 297.]

Implicit in the statement is the notion that a court might declare a covenant invalid even if it is reasonable in scope and duration, does not have a pernicious objective, and creates neither a monopoly nor an unreasonable restraint of trade. In brief, merely because it does not like a covenant, a court may find it invalid. This implication infects the usefulness of such covenants and represents an unwarranted intrusion of the judiciary in private transactions. The statement also points up the problem of blurring the contractual and property aspects of the covenant. Supra at 221-222, 579 A.2d at 300-301. Fairly read, the factors are not relevant to the determination of enforceability, as the Court initially indicated, but to the determination whether the appropriate relief is the award of damages or an injunction. See Welitoff v. Kohl, 105 N.J. Eq. 181, 189, 147 A. 390 (E. & A. 1929).

The decided cases suggest that changed circumstances justify the refusal to enforce an otherwise-enforceable covenant only when the change defeats the covenant’s purpose. Thus, in Doo, supra, 265 Cal. App.2d at 756, 71 Cal. Rptr. at 481, a claim of changed circumstances could not defeat a restrictive covenant against a grocery store as long as the benefitted party continued to operate a competitive store on another property. Analogous New Jersey cases imply a similar conclusion. In Weinstein v. Swartz, 3 N.J. 80, 89, 68 A.2d 865 (1949), when business development elsewhere did not affect the residential character of the neighborhood in which the burdened property was located, the Court recognized the continuing validity of restrictions limiting the use of the property to a single-family residence. Similarly, in Leasehold Estates v. Fulbro Holding Co., 47 N.J. Super. 534, 565, 136 A.2d 423 (App.Div. 1957), the court refused to enforce a 103-year-old covenant limiting the use of the front of an alley to barns and stables because enforcement would not provide the “contemplated benefit to the covenantee.”

Perhaps the majority’s opinion is best read as holding that Davidson is entitled to damages but not an injunction if the covenant was reasonable when formed, but now adversely affects the public welfare of the people of New Brunswick. See Gilpin v. Jacob Ellis Realties, 47 N.J. Super. 26, 31-34, 135 A.2d 204 (App.Div. 1957). Such a holding would ensure that Davidson will not be “left without any redress; * * * [it will be] given what plaintiffs are given in many types of cases – relief measured, so far as the court reasonably may do so, in damages.” Id. at 34, 135 A.2d 204.

Nothing in the record provides any basis for finding that in the six years that elapsed between 1980, when Davidson sold to Katz, and 1986, when Katz sold to the Authority, circumstances changed so much that they render the covenant unenforceable. The record is devoid of any showing that anything has happened since 1980 that has deprived the Elizabeth Street store of the covenant’s benefit. Notions of “changed circumstances” and the “public interest” thinly veil the Authority’s attempt to avoid compensating Davidson for the cost of the lost benefit of an otherwise-enforceable covenant. I am left to wonder whether the majority would so readily condone the Authority’s taking of Davidson’s property if the interest taken were one in fee simple and not a restrictive covenant. It is wrong to take Davidson’s covenant without compensation just as it would be wrong to take its fee interest without paying for it. Shopkeepers in malls throughout the state will be astonished to learn that noncompetition covenants that they have so carefully negotiated in their leases are subject to invalidation because they run counter to a court’s perception of “changed circumstances” and the “public interest.”

-II-

For me the critical issue is whether the appropriate remedy for enforcing the covenant is damages or an injunction. Ordinarily, as between competing land users, the more efficient remedy for breach of a covenant is an injunction. R. Posner, Economic Analysis of Law 62 (1986) (Posner); R. Epstein, Notice and Freedom of Contract in the Law of Servitudes, 55 S.Cal.L.Rev. 1353-67 (1962); Calabresi and Melamed, Property Rules, Liability Rules, and Inalienability: One View of the Cathedral, 85 Harv.L.Rev. 1089, 1118 (1972) (Calabresi and Melamed). But see Posner, supra, at 59; Calabresi and Melamed, supra, at 119 (discussing situations in which damages are a more efficient remedy than an injunction). If Katz still owned the George Street property, the efficient remedy, therefore, would be an injunction. The Authority, which took title with knowledge of the covenant, is in no better position than Katz insofar as the binding effect of the covenant is concerned. Although an injunction might be the most efficient form of relief, it would however deprive the residents of access to the George Street store.

The economic efficiency of an injunction, although persuasive, is not dispositive. The right rule of law is not necessarily the one that is most efficient. Saint Barnabas Medical Center v. Essex County, 111 N.J. 67, 88, 543 A.2d 34 (1988) (Pollock, J., concurring); see also R. Coase, The Problem of Social Cost, 3 J. Law & Econ. 1, 19 (1960). In other cases, New Jersey courts have allowed cost considerations other than efficiency to affect the award of a remedy.

For example, in Gilpin, supra, 47 N.J. Super. 26, 135 A.2d 204, the court refused to approve an injunction, but upheld an award of damages to the victim of a breach of a covenant. The property right at issue was a covenant restricting the building of any structure more than fifteen feet tall within four feet of one of the parties’ common boundaries. Defendant, a builder, was the successor to the land of the original covenantor. Plaintiff succeeded to ownership of the land originally benefitted by the covenant. Defendant and plaintiff were neighboring landowners. Defendant breached the covenant. Remodeling the structure would have cost defendant $11,500. The trial court had found that the breach harmed plaintiff to the extent of $1,000 in damages. Invoking the “doctrine of relative hardship,” the Appellate Division held that the differences in these two figures were “so grossly disproportionate in amount as to justify the denial of the mandatory injunction.” 47 N.J. Super. at 35-36, 135 A.2d 204. At the same time, the Appellate Division upheld the $1,000-damages award to plaintiff. Id. at 36, 135 A.2d 204. Thus, the court concluded that the appropriate remedy for enforcing the covenant was an award of damages, not an injunction.

Injunctions, moreover, are ordinarily issued in the discretion of the court. Id. at 29, 135 A.2d 204. Hence, “[t]he court of equity has the power of devising its remedy and shaping it so as to fit the changing circumstances of every case and the complex relations of all the parties.” Sears, Roebuck & Co. v. Camp, 124 N.J. Eq. 403, 412, 1 A.2d 425 (E. & A. 1938) (quoting Pomeroy, Equity Jurisprudence § 109 (5th ed. 1941)). In the exercise of its discretion, a court may deny injunctive relief when damages provide an available adequate remedy at law. See Board of Educ., Borough of Union Beach v. N.J.E.A., 53 N.J. 29, 43, 247 A.2d 867 (1968).

In the past, however, an injunction in cases involving real covenants and equitable servitudes “was granted almost as a matter of course upon a breach of the covenant. The amount of damages, and even the fact that the plaintiff has sustained any pecuniary damages, [was] wholly immaterial.” J.N. Pomeroy, Equity Jurisprudence, § 1342 (5th ed. 1941). The roots of that tradition are buried deep in the English common law and are not suited for modern American commercial practices. In brief, the unswerving preference for injunctive relief over damages is an anachronism.

At English common law, as between grantors and grantees, covenants running with the land violated the public policy against encumbrances. See Powell, supra, § 670 n. 27 (citing Keppell v. Bailey, 39 Eng.Rep. 1042 (Ch. 1834)). The policy becomes understandable on realizing that England originally did not provide a system for recording encumbrances, such as restrictive covenants. See Berger, A Policy Analysis of Promises Respecting the Use of Land, 55 Minn.L.Rev. 167, 186 (1970). Without a recording system, a subsequent grantee might not receive actual or constructive notice of such a covenant. As the Court points out, “[a]dequate notice obliterated any express requirement of ‘touch and concern.’” Ante at 204, 579 A.2d at 292.

For centuries, New Jersey has provided a means for recording restrictive covenants. Hence, the policy considerations that counselled against enforcement of restrictive covenants at English common law do not apply in this state. In the absence of an adequate remedy at law, moreover, the English equity courts filled the gap by providing equitable relief, such as an injunction. Tulk, supra, 2 Phil. 774, 41 Eng.Rep. 1143 (discussed by the majority, ante at 204, 579 A.2d at 292.) In this state, unlike in England, covenants between grantor and grantee are readily enforceable. Roehrs v. Lees, 178 N.J. Super. 399, 429 A.2d 388 (App.Div. 1981) (covenant between neighboring property owners arising from a grantor-grantee relationship between original covenanting parties enforceable; matter remanded to trial court to determine whether damages or injunction was appropriate); Gilpin, supra, 47 N.J. Super. at 29, 135 A.2d 204. Hence, the need for injunctive relief, as distinguished from damages, is less compelling in New Jersey than at English common law, where damages were not always available. I would rely on the rule that a court should not grant an equitable remedy when damages are adequate. N.J.E.A., supra, 53 N.J. at 43, 247 A.2d 867.

Here, moreover, the Authority holds a trump card not available to all other property owners burdened by restrictive covenants – the power to condemn. By recourse to that power, the Authority can vitiate the injunction by condemning the covenant and compensating Davidson for its lost benefit. That power does not alter the premise that an injunction is generally the most efficient form of relief. See Calabresi and Melamed, supra, at 1118; Posner, supra, at 62. It merely emphasizes that the Authority through condemnation can effectively transform injunctive relief into a damages award. Arguably, the most efficient result is to enforce the covenant against the Authority and then remit it to its power of condemnation. This result would recognize the continuing validity of the covenant, compensate Davidson for its benefit, and permit the needy citizens of New Brunswick to enjoy convenient shopping.

Forcing the Authority to institute eminent-domain proceedings conceivably would waste judicial resources and impose undue costs on the parties. A more appropriate result is to award damages to Davidson for breach of the covenant. That would be true, I believe, even against a subsequent grantee that does not possess the power to condemn.

Money damages would compensate Davidson for the wrong done by the opening of the George Street supermarket. Davidson would be “given what plaintiffs are given in many types of cases – relief measured, so far as the court reasonably may do so, in damages.” Gilpin, supra, 47 N.J. Super. at 34, 135 A.2d 204. The award of money damages, rather than an injunction, might be the more appropriate form of relief for several reasons. First, a damages award is “particularly applicable to a case, such as this, wherein we are dealing with two commercial properties * * *.” Id. at 35, 135 A.2d 204. Second, the award of damages in a single proceeding would provide more efficient justice than an injunction in the present case, with a condemnation suit to follow. Davidson would be compensated for the loss of the covenant and the needy residents would enjoy more convenient shopping. That solution is both efficient and just.

I can appreciate why New Brunswick residents want a supermarket and why the Authority would come to their aid. Supermarkets may be essential for the salvation of inner cities and their residents. The Authority’s motives, however noble, should not vitiate Davidson’s right to compensation. The fair result, it seems to me, is for the Authority to compensate Davidson in damages for the breach of its otherwise valid and enforceable covenant.

PROBLEMS

There is a group of neighbors who wish to contract to prevent commercial development of any of their lands.

- How might they do this to ensure the agreement runs with their lands?

- What is the minimum they need to do in order to create agreements enforceable against successors?

- Give an example of a successor who would not be in strict vertical privity with his or her predecessor.

- What needs to be shown for a successor to sue an original contracting party who develops commercially?

Answers

1. How might they do this to ensure the agreement runs with their lands?

The answer needs to include something ensuring horizontal privity. Full credit if you say they need to enter a strawman transaction with a lawyer and record the agreement. 1/2 credit if you just list the elements for the burden to run with some explanation but without highlighting what exactly they need to do to achieve horizontal privity (h.priv., v. priv., writing, intent, notice, touch and concern).

2. What is the minimum they need to do in order to create agreements enforceable against successors?

They just need to put it in writing and record or otherwise provide for notice. The key here is that they don’t need to achieve horizontal privity to create an enforceable equitable servitude (injunction suit).

3. Give an example of a successor who would not be in strict vertical privity with his or her predecessor.

The tenant of a landlord. Any example where the predecessor retains an interest will work. (Life Tenant with a reversion in the grantor rather than a remainder interest in someone else.)

4. What needs to be shown for a successor to sue an original contracting party who develops commercially?

Only that the benefit runs: Writing, intent, touch and concern. The point is that you don’t have to show that the burden runs – i.e., no need for notice. If you mention vertical privity, that’s fine, but it’s generally not needed to sue for an injunction.

6.1.2. Implied Covenants

Sanborn v. McLean,

206 N.W. 496 (Mich. 1925).

Clark, Emmons, Bryant & Klein, of Detroit, for appellants.

Warren, Cady, Hill & Hamblen, of Detroit, for appellees.

Wiest, J.

Defendant Christina McLean owns the west 35 feet of lot 86 of Green Lawn subdivision, at the northeast corner of Collingwood avenue and Second boulevard, in the city of Detroit, upon which there is a dwelling house, occupied by herself and her husband, defendant John A. McLean. The house fronts Collingwood avenue. At the rear of the lot is an alley. Mrs. McLean derived title from her husband, and, in the course of the opinion, we will speak of both as defendants. Mr. and Mrs. McLean started to erect a gasoline filling station at the rear end of their lot, and they and their contractor, William S. Weir, were enjoined by decree from doing so and bring the issues before us by appeal. Mr. Weir will not be further mentioned in the opinion.

Collingwood avenue is a high grade residence street between Woodward avenue and Hamilton boulevard, with single, double, and apartment houses, and plaintiffs, who are owners of land adjoining and in the vicinity of defendants’ land, and who trace title, as do defendants, to the proprietors of the subdivision, claim that the proposed gasoline station will be a nuisance per se, is in violation of the general plan fixed for use of all lots on the street for residence purposes only, as evidenced by restrictions upon 53 of the 91 lots fronting on Collingwood avenue, and that defendants’ lot is subject to a reciprocal negative easement barring a use so detrimental to the enjoyment and value of its neighbors. Defendants insist that no restrictions appear in their chain of title and they purchased without notice of any reciprocal negative easement, and deny that a gasoline station is a nuisance per se. We find no occasion to pass upon the question of nuisance, as the case can be decided under the rule of reciprocal negative easement.